What Hollywood can teach Magazine Writers

How is it that a screenwriter in Hollywood can get paid a six figure salary by simply giving a movie studio the option to see their work before anyone else does? How are some authors able to convince publishers to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars on their book advances? And, why is it that freelance journalists are almost perpetually broke and rarely make more than two dollars a word?

How is it that a screenwriter in Hollywood can get paid a six figure salary by simply giving a movie studio the option to see their work before anyone else does? How are some authors able to convince publishers to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars on their book advances? And, why is it that freelance journalists are almost perpetually broke and rarely make more than two dollars a word?

The answer to these questions lies in the history of these different industries. At one point most journalists had staff jobs at newspapers or on the mastheads of magazines. They were expected to produce a lot of material, had stable salaries and their work pretty much always belonged to the companies they worked for. Hollywood and book publishing were different. No one was guaranteed work. Writers came up with their own ideas and then sold them to movie studios and publishers on a freelance basis. They hired agents who knew the industry, looked out for their interests and held auctions to drive up the price of their work. Book publishers and studios paid the increasingly high prices and still turned a profit.

In the last decade the rise of the internet led magazines and newspapers to drastically reduce the size of their staffs. Now they produce a lot more content but have to rely on freelance labor to produce it. And here is where the problem started. They kept the old model of keeping all the rights for themselves, but never offered their freelancer workers stability in exchange. For some reason–most likely the general sense of inferiority that most writers feel–freelance journalists never fought to have their work sell at a market rate. They often gave up their movie rights and accepted kill fees and chronically late payments by the publications they worked for. The major publishing houses had no reason to raise rates and today they spend less than .6% of their gross revenues paying writers. Meanwhile, those publishers post quarterly reports that reflect multi-billion dollar valuations.

Today it’s almost impossible to make a living as a freelance writer without having a job on the side or a generous spouse to support your work. Even the most successful freelancers out there–I count myself among their numbers–know that you don’t make money from magazines, but from the book and TV deals that come afterwards. This doesn’t have to be the case. Being a journalist could actually be a middle class profession again. There’s a way to change the industry for the better.

Writers need to take a page from Hollywood and start fighting for better pay and stronger copyright. They need to hire agents to represent their very best work and force multiple publications to bid for the right to publish it. Of course, magazine publishers will resist at first. Some writers will lose assignments in the process. However, it will soon become clear to them that in order to publish the best stories magazines will have to give writers a cut of advertising revenues. When you take into account the incredibly high rate that magazines sell advertising for, this might mean that some writers could command as much as $20 for every published word–which would put them on par with what has become industry standard 10% royalty rate among book publishers.

For the last few weeks I’ve been talking to some of the highest profile literary agents and writers in the country in an attempt to suss out how feasible it would be to start a literary agency for magazine writers. Instead of pitching a magazine, writers would pitch the agency. And the agency would work for them to get the very best rate possible. For this to work, it will need to attract the best writers in the country to join the effort. It will need to become a broker of amazing ideas: an exclusive destination for top-notch reporting.

In other words, it will have to be the sort of effort that made being a script writer or book writer a viable profession. It is something that we could make happen together.

__

UPDATE: There are a few ways to fight back. I recently started offering an online video course teaching some of the tricks that I use to negotiate better contracts, and grow my freelancing business from nothing to becoming a New York Times bestselling author. It might be useful for you. Check it out.

Brian William and the Myth of the Intrepid Tv...

For almost a decade NBC anchor Brian Williams has repeated a story that when he was reporting from Iraq the helicopter he was flying in was hit by a rocket propelled grenade.

For almost a decade NBC anchor Brian Williams has repeated a story that when he was reporting from Iraq the helicopter he was flying in was hit by a rocket propelled grenade. It turns out that he was lying and for the last week he has been at the center of a media whirlwind with people across the country calling for his resignation. After he apologized, investigative sleuths dug deeper into other statements that he has made over the years and it appears that quite a few of his stories don’t check out. A lot of digital ink has been spilled on the affair, but I think that there is a larger issue at stake that has a lot more to do with the American public’s lack of knowledge about the media rather than Williams’ own statements.

Television is a medium for entertainment, and just about everything that appears on it is carefully produced behind the scenes. While it often appears that television hosts are investigating black markets, on the front lines of a war, or painstakingly filing FOIA requests to uncover government corruption on their own, the truth is that while the information they may present might be accurate and fact checked, the representation you see is almost always a fabrication. Before an anchor appears in the field producers, researchers, fixers and investigators have already tracked down leads, scouted potential locations, shot B-roll and prepped the interviewees and had them fill out release forms. When the anchor arrives on the scene the story is wrapped up in a tight little package and most of the time all the host has to do is shoot a few hours of film and then fly hope to begin prepping another story. The host gets the credit for the story and the TV viewing audience gets to identify with a single personality from one broadcast to another.

The end result is that TV journalists–and to some degree the big names in print and radio as well–are able to craft an outsized image of intrepid journalists working under dangerous conditions. They seem to be able to accomplish amazing feats of investigation almost every night as they scoot around the world and are always in the right place at the right moment. It’s all fiction. Hosts are characters, not journalists.

This holds true for any news personality you see. Whether it’s Anderson Cooper , Shane Smith, Lisa Ling, Diane Sawyer or Mike Rowe all of them benefit and take credit for the work of their staff. These hosts are often called “the talent” by the channels they work for, much to the chagrin of the people who actually do the groundwork that enables the veneer.

Given that this is the general state of the media, is it really any shock that Williams might make up a story about being shot at while on the job? The whole career path is based on the fiction that he is always at the center of the action. The job description includes him helicoptering into the middle of a developing story, shooting a few minutes and then flying back out to safety. The stories that he made up of being in the middle of the action help to cement his reputation with the general public and are simply an extension of the sorts of news shows that viewers demand.

We want to see hosts who are in the middle of things. We want to believe that the journalists that we have a nightly relationship with on the screen are the real deal. But it’s an impossible image to sustain. There is no way that Williams, or any other host, could actually do that amount of work even if they are supremely talented, as I have no doubt Williams is. I’ve been an investigative journalist for almost ten years and while I have been in the middle of “the action” a few times–held up by child soldiers, shadowed by hit men, and confronted organ traffickers–those events are extremely rare. Most of the time I sit at a desk and do the ground work for my stories all on my own. A full investigation can take six months to a year and only result in one tantalizing anecdote. The reason that Williams and other hosts are able to present the image that they do is because there are dozens of people like me working behind them to set up the scenes.

Williams shouldn’t have lied. It did a disservice to the soldiers who actually were under fire that day. However, if the media is going to crucify him for his accounts they should also take this time to acknowledge that much of what the see on TV isn’t exactly true, either.

How kill fees ruin writers, hurt magazines and destroy...

Just about every journalism contract contains a clause called a “kill fee” that states that if the magazine decides not to run a particular story then it will pay out only a fraction of the agreed upon rate.

Just about every journalism contract contains a clause called a “kill fee” that states that if the magazine decides not to run a particular story then it will pay out only a fraction of the agreed upon rate. The writer is then free to sell the story to another publication. The logic behind this policy is that the clause is insurance so that a writer won’t simply accept a contract and then write a half-baked and poorly reported story and then run off with the full payment. Unfortunately the kill fee serves a much more diabolical role in the modern magazine industry. Not only it is bad for writers, it also exposes magazines to potential libel suits and degrades the overall quality of journalism in America.

Last week I had a conversation with a former editor at the New York Times Magazine who told me that they kill between 1/4 and 1/3 all assignments they issued to their on-contract writers. The magazine killed a much higher percentage of stories that they assigned to freelancers who weren’t already on the masthead.

While a kill fee is supposed to be insurance against bad writing, the NYT magazine was using it in a different way. A story can be killed for literally any reason: not only because of poor quality, but because an editor no longer thinks an idea is fresh, or that a character doesn’t “pop” on the page, or the piece was covered in another magazine between the time it was assigned and then scheduled to be published. (Those are three reasons that I’ve had stories killed over the years). Instead publications now routinely use the kill fee system as a way to increase the overall pool of material they can choose from to publish. They intentionally over-assign and account for a certain percentage of killed pieces in advance. Stories that are on the bottom of their list don’t make the cut. This policy has nothing to do with the quality of what a writer submits, rather a business model that intentionally transfers risks reporting onto the backs of their authors.

Anyone who has written for a major publication knows that there is a wide gap between what a writer pitches to a magazine and what they encounter when they are actually reporting a piece in the field. This is the basic disconnect between any proposal and the reality on which that proposal hangs. There is no guarantee that when a reporter gets out into the field that they will find the juicy narrative anecdotes that will make a piece sing on the page. Still, the only way to find out what is happening in the world is to actually do the work, travel to the locations, report the hell out of what you find and then try to write it up.

Let me give an example. A year or two ago I took an assignment with the NYTimes magazine about an epidemic of counterfeit drugs in India that had been reported on by several NGOs. The pitch went well and I flew across the world to look for evidence. When I got to Delhi, however, it turned out that the issue was essentially made up by major pharmaceutical companies in order to keep their market share secure from loose Indian patent laws. It was a different issue from the one I pitched, and the editor wasn’t interested in the actual facts. I spent a month searching for evidence of a large-scale counterfeit market that Big Pharma had promised but couldn’t find anything strong enough. When I came back to America I sent the best draft of the piece I could to my editor. He didn’t like it. So I rewrote it. He wanted stronger anecdotes, so I rewrote it again. Over the course of the next seven months I rewrote the draft at least 9 times from scratch looking for better angles and more powerful anecdotes. In the end the editor, who never really gave me much useful feedback despite my endless rewrites, killed the piece. The NYTimes issued me a 25% fee as per the terms of their contract. I had spent the better part of a year working on the story.

There are two major problems with this. First, I worked in good faith that the story I published would eventually appear in the pages of the magazine. If the same editor had hired a painter to slap a new coat of paint on his house, but at the end of the day decided to that the color wasn’t quite right, he would still have to pay the painter a full rate for the work that he did do. Apparently the same rules don’t apply to writers. Instead I had spent a great deal of effort on a piece that not only would never appear in print, but that I didn’t even receive the expected fee for.

For those unconcerned about writer’s finances lets talk about the second problem. Think instead of what this does to a journalist in the field whose paycheck, rent, insurance, loan payments and everything else literally depends on the salaciousness of their story. The journalist may have an incentive to take extra risks during their reporting–going to increasingly hostile and difficult terrain in the hopes of finding the right salacious anecdote. Or, perhaps even more disheartening, they might decide that the only way to get full pay is to simply make things up. In the last decade the media has been racked by one journalism scandal after another where poorly reported stories resulted in lawsuits and made the public at large distrust major news organizations. Just this year a Rolling Stone reporter completely failed to check a rape allegations at UVA resulting in what will likely be a costly libel lawsuit. Would it be any shock if the reporter worried that her story might get killed if her details weren’t cover worthy enough that she was seduced by the perfect anecdote? Who is to say that I wouldn’t have been able to save my story, seven months of work and 75% of my income if I had just played a little more fast and loose with the anecdotes that I came up with when I was reporting in India? Certainly I had incentive to do so. The only thing that stopped me was a general sense of propriety in my work.

If, on the other hand, publications paid people for the work that they actually conduct in the field, then there would be less financial pressure to take extra risks or make up facts while on assignment. Publications, in turn, would have to worry a little bit less about the safety of their reporters and the quality of journalism that they publish. It’s not as if the major magazines don’t have enough money to pay writers for the work they do in the field. Last year the New York Times posted a profit of $92 million. Conde Nast, the publisher of GQ, Wired, Vanity Fair and the New Yorker in turn, spends less than 1% of its gross revenues on words.

The policy of magazines paying almost nothing for killed stories needs to change. When a reporter goes into the field they need to be secure in the knowledge that the magazine has their back even if the world turns out to be more complex than the original pitch. Killing the kill fee would be good for writers and good for the magazines they write for.

__UPDATE: This, of course is pretty bad news for freelancers, but there are a few ways to fight back. I recently started offering an online video course teaching some of the tricks that I use to negotiate better contracts, and grow my freelancing business from nothing to becoming a New York Times bestselling author. It might be useful for you. Check it out.

Are you Pitching to Silo or a Market?

At this point it’s no secret that writers get a pretty lousy deal in the publishing business. Every day someone asks me if there’s a way to fight back. In fact, there’s one common practice that writers take on that hobbles them from the very start, and it’s our fault that the problem exists at all. Most journalism schools, editors, and old-time-freelancers advise new writers to only pitch one magazine at a time when they are trying to sell a story. In turn, most editors assume that pitches are exclusive material and will go as far as to say that they wont even consider an idea if another publication is reviewing it as well. This is called “silo pitching”, and it’s the surest route to penury for a writer.

At this point it’s no secret that writers get a pretty lousy deal in the publishing business. Every day someone asks me if there’s a way to fight back. In fact, there’s one common practice that writers take on that hobbles them from the very start, and it’s our fault that the problem exists at all. Most journalism schools, editors, and old-time-freelancers advise new writers to only pitch one magazine at a time when they are trying to sell a story. In turn, most editors assume that pitches are exclusive material and will go as far as to say that they wont even consider an idea if another publication is reviewing it as well. This is called “silo pitching”, and it’s the surest route to penury for a writer.

That silo pitching is the standard method to market story ideas to publications is indicative of just how scared writers are of the people they work for. Most writers tell me that they would never take their ideas out to multiple publications because they worry they might be blacklisted and never find work again. Loyalty, they say, also has its perks because a good editorial relationship might secure future assignments. Unfortunately the loyalty that writers feel to their editors is rarely reciprocated. At the mainstream magazines editors almost always take a very long time to respond to pitches. Even after an initial expression of interest, an assignment can take months—yes months–to finally receive a green light. Sometimes editors don’t even bother to respond in the first place which means that a good idea that might have found a home at another magazine could malinger and die in the inbox of the first editor you sent it to.

A more serious problem with silo pitching is that by extending exclusivity to a single magazine in advance means the the writer has effectively given up any ability to negotiate the contract when it comes time to sign. There’s never a chance to allow the market to value a writers’ work by getting input from multiple potential buyers. Instead the writer has almost no option than accept whatever deal the magazine puts up. This is why bad deals are now the industry standard. Forget the lamentable payment terms, most magazines now also suck away film and reprint rights, offer low kill fees, and won’t pay their writers until months, and in some cases, years after the magazine has appeared in print.

Silo pitching completely violates any attempt for a writer to receive a market value for their work.

In Hollywood and in book publishing exclusivity deals are well compensated. A good script writer might make upwards of $50,000 a year from a single studio just so that they have the right of first refusal on whatever they come up with. That journalists give away this right by default shows just how sick this business actually is.

The solution, of course, is simple. It’s called “market pitching,” which is exactly the model that exists in Hollywood and book publishing. In a market pitch a writer puts together their very best material (I can’t stress this enough: your pitch needs to be a work of art) and then takes it out to every potential publication on the market. While each publication might get a slightly tweaked version of the story, the idea is fairly straight forward: if the idea is good enough you will get multiple offers. At the very least this might mean the difference between a feature that runs 5000 words or something that runs as little more than a long paragraph in the front of the book.

Let me give you an example. A few years ago I pitched a story to thirty magazines about the death of a single mediatory in the mountains of Arizona. After far too long, I received an offer from the Atlantic for a 1000 word piece that would run in the front of the magazine. It wasn’t nearly long enough for the story that I wanted to write. Luckily I’d also pitched Playboy and they came back a day later with an offer to run a full feature at 6500 words. It was more than six times the money. If I had only pitched the Atlantic I would have never gotten the deal that eventually matured into my forthcoming book “A Death on Diamond Mountain”. Even worse, if I had only written to the New Yorker and waited for months for them to never respond, I would never have written a story at all.

Of course, another advantage of market pitching is that it also give you leverage to negotiate publishing contracts. Standard contracts at different magazines might vary widely, and some publications are more open to negotiating contract points than others.

At the very least, market pitching offers a writer the ability to say that they got the best deal available for their work. If you pitch 20 magazines and only one gives an offer, then maybe the deal they give you really IS what your story was worth. Then again, if three or four offers come in then you have the ability to take the best deal on the table. Now think about what happens if you come across an important story that every magazine wants to have in its pages. Something that will likely steer the national conversation for a few days or weeks? There’s no reason why you couldn’t hold an auction and have magazines bid for the right to have you. In that case the sky is the limit for payment because the magazine knows that it will be able to sell more advertisements–often for upwards of six figures each–if they have your story in their pages. It’s entirely possible that a writer in an auction could receive hundreds of thousands of dollars for the right story.

Of course, writers are incredibly reticent to try market pitching because it seems risky. Writers cherish their relationships with editors and often worry that playing one magazine off of another for a better deal will put them on some sort of black list. I admit that this is possible. But any editor that doesn’t understand the pressures that freelancers face is probably not worth working with anyway. Risking the ire of one person is not a reason to submit yourself to a life of poverty. Instead, take heart in a depressing fact about the publishing industry today: most magazines have an incredibly high turnover rate. While you may cherish your relationship with a particular editor, most editors wont last in their positions more than a few years without moving on. Call me cynical if you like, but in my ten years as a freelancer I’ve learned that just about anyone you upset will be at another publication pretty soon, or, more likely, end up in an entirely different field.

It’s far more important to cultivate a market strategy than worry about any one particular person’s feelings. After all, it’s not personal. It’s business.

___

UPDATE: This, of course is pretty bad news for freelancers, but there are a few ways to fight back. I recently started offering an online video course teaching some of the tricks that I use to negotiate better contracts, and grow my freelancing business from nothing to becoming a New York Times bestselling author. It might be useful for you. Check it out.

The case for 20$ per word

WARNING: I’m about to make statement that is so revolutionary that you might begin to question my sanity. It’s a goal for writers that will seem not only unattainable, but impossible: as if I’ve been living on an entirely different planet. What I’m going to propose is that writers at mainstream magazines–particularly the ones in the Conde Nast empire, but also Wenner Media, and Hearst–should be paid not only a living wage, but one that values them in the same way that magazines sell their writing to advertisers. I’m going to suggest that writers at the top magazines in America should make at least $20 per word.

WARNING: I’m about to make statement that is so revolutionary that you might begin to question my sanity. It’s a goal for writers that will seem not only unattainable, but impossible: as if I’ve been living on an entirely different planet. What I’m going to propose is that writers at mainstream magazines–particularly the ones in the Conde Nast empire, but also Wenner Media, and Hearst–should be paid not only a living wage, but one that values them in the same way that magazines sell their writing to advertisers. I’m going to suggest that writers at the top magazines in America should make at least $20 per word.

The number is ten times the standard going rate of $2 that most magazines pay (check out current rates at my crowdsourced Google Doc). However, given the current economics of the industry, I have to argue that it also is the only fair rate for our work after you account for how much print advertisements sell for. Take for instance the fact that average rate that Conde Nast sells a single page of advertising to their clients for is about $130,000. Magazines vary pretty widely in their page count, but over the last few days I’ve counted the adds in about a dozen different issues and the smallest magazines have about 30 ads, the fattest more than 100. For argument’s sake, lets saw that the average Conde Nast magazine has 50 pages of advertising. After they give their clients a steep discount, they reap about $70,000 per page in revenues. It’s pretty conservative to say that a run of the mill Conde Nast magazine makes at least $3.5 million per issue. At the very most, the fattest mags in the empire run about 40,000 words for a total payout of $80,000 to writers. That’s only 1% of its gross revenues dedicated to words. However, if you were to ask just about any reader I’m pretty sure that they would tend to agree that words and stories make up more than 1% of the value of a magazine.

(At some point people here are gonna say, “what about the New Yorker?” they barely have any ads. I admit they’re a bit of a special case, but bear with me. If you average the payouts across all of Conde Nast they you also have to include Glamour, Vogue, Self and Lucky, which more or less are simply books full of ads with very little original content at all.)

The really radical thing that I’d like to suggest is that the budget for writers should reflect their actual value to the industry. To figure out what that is I’m going to borrow a page from the book publishing business–something that as the author of two books, I know a little bit about. In the publishing contracts that I’ve signed I get paid between 8% and 12.5% of the gross revenues that my books sell. The remaining 87.5% – 92% of the revenues are enough to fully fund distribution, pay editors, print copies of the book, employ a marketing staff and everything else that I didn’t list here. Indeed, that split still allows book publishers to make pretty decent revenue overall.

So how did I come up with $20 per word? Multiplication. If we were to make just 10% of the gross revenues of a given magazine then we would earn at least $20 for every word we publish.

Think about it. We’re the ones who come up with the ideas for our stories and execute them. Sometimes we travel to potentially dangerous locations–I can remember at least one story I wrote for Wired where I was surrounded by men with guns and swords who would have been happy to take my life if I’d said the wrong thing. They might cover our travel expenses, but we craft the narratives that become movies and book deals. And we always run the risk of having our stories killed and not getting paid for our work. We deserve at least the same fair shake that book writers get.

Of course some people will crow the common fallacy that the magazine business is dying. How on earth could writers ask for a larger slice of the pie when print pubs are shutting their doors left and right? Well, according to their own press releases Conde Nast is not embattled. It’s actually turning a profit. There are more ad pages every year since the recession. There’s more internet presence. And even the New Yorker, which traditionally looses about $20 million a year, is in the black. Need more proof? Lets look at its executive leadership. The company is owned by Samuel Newhouse Jr. whose current net worth is $8.2 billion. That’s a lot of money. It’s enough money to Conde Nast to have a huge architecturally amazing building in Times Square–the most expensive real-estate in the country and then buy a second 104 floor office building on Wall Street with over a million square feet of office space. Meanwhile, if you pooled all of the payouts to writers by Conde Nast on any given year into one pool, we would barely be able to collectively afford the median price for a three bedroom flat in the same city.

Journalists and writers have long suffered from an inadequacy complex. The assumption is that it’s an honor to break into the mainstream publishing business, and they mostly just sign the contracts offered to them without bothering to offer a counter proposal or even ask for a higher rate. Over the years this attitude has allowed publishers to assume that words are not very valuable on their own. This is our own fault. But if we started to demand out fair share and turning down terrible contacts then perhaps we’d be able to show magazine publishers that our words are worth more than just 1% of what they sell our words for to other people.

___

UPDATE: This, of course is pretty bad news for freelancers, but there are a few ways to fight back. I recently started offering an online video course teaching some of the tricks that I use to negotiate better contracts, and grow my freelancing business from nothing to becoming a New York Times bestselling author. It might be useful for you. Check it out.

Crowdsourcing Journalism Rates

For the last few years I’ve been keeping a list of editors, word rates, contact details and brief notes on different magazine and website editors with my colleagues at the Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism. It was crowdsourcing on a relatively small scale to help us figure out where the best home for our writing would be. However, I’ve come to realize that the list might also be useful for another, perhaps more noble goal. So I’ve scraped off the personal and identifying details and added a few new columns.

For the last few years I’ve been keeping a list of editors, word rates, contact details and brief notes on different magazine and website editors with my colleagues at the Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism. It was crowdsourcing on a relatively small scale to help us figure out where the best home for our writing would be. However, I’ve come to realize that the list might also be useful for another, perhaps more noble goal. So I’ve scraped off the personal and identifying details and added a few new columns.

I’m throwing the database online and inviting writers from all over the world to add what they know about the size of the market. Help out and contribute by clicking on this link. Lets figure out what every magazine pays per word, how many features are in each book, and what they charge for advertising.

It’s a Google Doc, and pretty easy to update and modify. I’ve filled in what blanks that I could, but someone should probably check my numbers. Most advertising rates are easy to find on company media kits like the one Conde Nast publishes publicly.

The reason for this, of course is that last week’s post on how much writing in America is actually worth struck a nerve. Many people were skeptical that magazines might really only pay out $3.6 million a year for their feature wells. The number seems absurdly small. And they might be right. Various commenters mentioned that the New Yorker alone must dish out almost $2 million annually on stories. Tom McGeveren wrote that his own publication (which turned out to be the newspaper the New York Observer) commanded a $3.5 million dollar budget on its own. However everyone seemed to understand the overall point writers get only a tiny sliver of the overall publishing revenues of mainstream magazines.

At the end of the day, almost no matter what set of numbers you crunch I’m almost certain that we will find that feature writing is such an insignificant amount that the advertising revenue from a single issue of one magazine should be able to cover the entire feature budget of all the magazines in America for an entire year. For instance: the December 2014 issue of Wired had 87 full page ads. At the prices listed in the media that would have been worth almost $15 million. Even if we assume that they dolled out a 50% discount to every advertiser, that’s still $7.5 million. The writer’s cut would have been less than $50,000, or about 0.6%.

A full market analysis should not rely only on back of the envelope math. Understanding the total value of words in America is going to require some fairly sophisticated work, as well as information from every sector of the writing world. Jonah Ogles, an editor at Outside, called for writers to get involved and start sharing data. So I’ve decided to follow up. Lets figure this thing out and maybe, just maybe, it will give us a tool to demand a slightly bigger piece of that overall publishing pie.

How much are words worth?

Writers tend to keep their thoughts in the realm of ideas rather than calculate the seemingly mundane matter of the mechanics of the trade. However, a few months ago I sat down in a Chinese restaurant with a friend of mine who writes for the New Yorker and we agreed to leave our narrative musings to the side and think about practicalities. We were going to try to figure out how much the printed word is worth in America today.

Writers tend to keep their thoughts in the realm of ideas rather than calculate the seemingly mundane matter of the mechanics of the trade. However, a few months ago I sat down in a Chinese restaurant with a friend of mine who writes for the New Yorker and we agreed to leave our narrative musings to the side and think about practicalities. We were going to try to figure out how much the printed word is worth in America today.

We wanted to calculate how many feature stories the top magazines in America assign every year, and how much they typically pay their writers for the assignments. The list was only going to be for the top publications in America–the ones that pay between $1.50-$5 per word and that comprise the top tier of journalism. These are the magazines that line the shelves of airport bookstores everywhere and the ones that we write for pretty regularly. Think The New Yorker, New York Times Magazine, Atlantic, Wired, Men’s Journal, Rolling Stone, Playboy, Vanity Fair, Mother Jones, O, The Atavist, and the dozen or so other magazines that sits on the tops of toilet tanks and the tables of dentist offices from Seattle to Orlando.

It was back of the envelope math at best, but as far as either one of us could determine, it was the first time anyone had tried to figure out how biG the pie was for long form freelance writing in America. There are hundreds of amazing writers in the country, delving into stories that drive the national conversation on everything from politics to the cult of celebrity to human rights abuses to cutting edge scientific and technological discoveries. These are the types of pieces that we make a living on, and ones that, frankly, we feel are important to write.

After ten minutes listing the average number of features in each magazine multiplied by the number of issues annually we had a number: 800. On average these stories would run at about 3000 words and pay $1.50 per word. It was only a ball-park estimate of the overall freelance writing market cap. But it was also a rather depressing one. Let me put this in bold so it stands out on the page.

The total market for long form journalism in major magazines in America is approximately $3.6 million. To put it another way: the collective body of writers earned less than Butch Jones, a relatively unknown college football coach, earned in a single year.

$3.6 million. That’s it. And the math gets even more depressing. If we assume that writers should earn the average middle class salary of $50,000 a year, then there’s only enough money in that pot to keep 72 writers fully employed. And, of course, those writers would have to pen approximately 11 well thought out and investigated features per year–something that both my friend and I knew was almost impossible.

Now, it could be that our estimate was a little low. But even if you double it–a number that is almost certainly far and above the size of the actual feature market, then we are collectively still barely scraping above $7 million paid out by magazines in word rates every year. According to Small Business Chronicle, the overall magazine publishing industry generates a total revenue of $35-40 billion a year. While that number includes lots of publications that are not in our sample, it does give at least some sense OF how small a slice of the pie writers actually earn.

Another way to figure out what the total publishing industry is worth is to check out the advertising rates that mainstream magazines publish on their websites. Take Wired, for example – not to pick on them, but because they are a representative of the some of the best journalism that exists in the country today. According to its media kit, a single page of advertising sells for $141,680. (And that’s not even the top of the market. A full page ad in GQ sells for more than $180,000). Multiply that by the number of full page ads in a single issue of Wired (about 30) and you get about $4.6 million in gross revenues per issue of the magazine.

Think about that for a second. A single issue of one major American magazine generates more gross revenue than what the entire magazine industry pays out in word rates over an entire year. If you figure that Wired spends about $30,000 on words in any given issue then a little more back of the envelope math says that words account for only 0.6% of the magazine’s revenue.

As a writer, this state of affairs horrifies me. I feel strongly that writers contribute more than just 0.6% of value to the overall magazine industry. Yes, magazines have a host of expenses–printing, distributing, editing, fact checking, office overhead and marketing all have a cost. But there is also something deeply sick in how little writers’ work is actually valued by the industry.

__

This, of course is pretty bad news for freelancers, but there are a few ways to fight back. I recently started offering an online video course teaching some of the tricks that I use to negotiate better contracts, and grow my freelancing business from nothing to becoming a New York Times bestselling author. It might be useful for you. Check it out.

**Stealth edit after some very good criticism **

A lot of people have raised good points at how my numbers are probably low. See the comments on Romenesko’s blog, for some whip-smart critique. I’ll address them in a future post, but I do want to make one quick correction in relation to online advertising rates that really wasn’t properly addressed above.

Most magazines list an aspirational price in their media kit and then give steep discounts to advertisers. I’m a bit sorry to keep picking on them, but I happen to have the December issue of Wired on my desk right now and I just recounted the ads. It was a fatter book than usual. There were 87 full page ads as well as numerous foldouts and a back cover. At the full media kit rate that is about $15 million in gross revenue for that issue. But they probably gave huge discounts to their clients. Lets say it was of 50% per page. That’s $7.5 million in gross advertising revenue. There were 5 features which means a total word count of about 25,000. Include FOB and other stuff it probably comes out to 40,000 words (I’m being generous). At the standard word rate ($2) that would come out to approximately 1% of that issue’s revenue.

**Stealth Edit #2**

Many people have suggested that 800 features is too low low. Lets try to come up with a fairer number. Most consumer magazines (think Details, GQ, Rolling Stone, Atlantic etc) run 2-3 features an issue. The number used to be 4-5, but it went down in the recession. Can we agree then that the average magazine would run about 36 features a year? The New Yorker runs 3 features a week, NYTm about the same. They have 50 issues a year and that makes for 150 stories each year for these sorts of magazines. Lets say there are 4 magazines like this (I can’t think of who they would be). The other 20 magazines run 36 features a year. So we revise the number of features as 1,320 per year. The total payout for these stories would come to about $8 million. Now consider that the December issue of Wired alone brought in $7.5 million even after a steep advertiser discount. One issue of one magazine still can cover the almost the entire cost of all features in America in a given year.

The Contract that Kills Journalism

I’m not sure when it started, but there’s a dangerous trend in the publishing industry to leech value from a writer’s work and make it almost impossible to earn a real living off of journalism. Yes, yes, we all know that media revenues are declining and even 100 year-old publications like The New Republic are teetering on the verge of extinction. For freelance journalists this has meant a general decline in word rates from a high in 1999 of $5/word at the top publications to as a low as $0.50/word at once-mighty institutions. Some publications now only pay their writers base on per-click, which as the venerable Erin Biba once said “is bullshit“.

I’m not sure when it started, but there’s a dangerous trend in the publishing industry to leech value from a writer’s work and make it almost impossible to earn a real living off of journalism. Yes, yes, we all know that media revenues are declining and even 100 year-old publications like The New Republic are teetering on the verge of extinction. For freelance journalists this has meant a general decline in word rates from a high in 1999 of $5/word at the top publications to as a low as $0.50/word at once-mighty institutions. Some publications now only pay their writers base on per-click, which as the venerable Erin Biba once said “is bullshit“.

But, I’m not writing to lament the decline of freelance revenues. I’m writing about something far more sinister: the way that publications today often demand that writers not only accept far less pay than they have received in the past, but also forfeit any rights over the work that they produce. While most new writers don’t think about much more than the pay they get for their words, a good story can go on to have a long life in several different mediums. The most lucrative of which are book, movie and TV deals. In those cases a writer could stand to make upwards of six figures for the research and narrative work that they put in up front. Indeed, many of the best movies of the last ten years started out as magazine stories (Argo, Hurt Locker, Erin Brockovich, Adaptation, Coyote Ugly, Boogie Nights, Big Love to name just a few).

Late last month I got ahold of Newsweek’s standard contract that one of my correspondents sent me. Hidden on the second page was this clause:

Assignment and Ownership of Intellectual Property. Writer hereby understands and agrees that all Articles submitted to, and published by, Company under this Agreement shall be considered works for hire as contributions to a collective work. This confers on the Company all right, title and interest, including copyright, in and to the Article(s), throughout the world. Further, to the extend any intellectual property right does not pass pursuant to a work for hire, Writer hereby assigns to Company all right, title, interest and copyright in and to the Article(s), and all previously submitted articles of Writer. In addition to the foregoing, Writer grants the Company a perpetual, worldwide, royalty-free, paid-up non-exclusive transferable license under copyright to reproduce, distribute, display, perform, translate or otherwise publish individually or as part of a collective work your Article(s) and all previously submitted articles to the Company, in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which it can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device, including without limitation the rights to archive, republish, edit, repackage or revise any Article in any manner as Company sees fit.

In short, this says that whatever you write for Newsweek is their property. It is as if they came up with the idea themselves, reported it in the field and typed it up on their own computers and the writer didn’t even exist. Work-for-hire contracts are always biased against an independent contractor, but this one is particularly onerous. Essentially this says that the writer has no copyright, no ownership, nothing whatsoever other than the $.50-$.75/word they were offering as “payment”. Never-mind that a typical investigative piece might take weeks, or even months to report, and that the final payment might well be below minimum wage, but as a writer you don’t even have the option to take the story idea that you developed and turn it into something bigger and potentially profitable. You can’t reprint it in a foreign publication, can’t sell the movie rights. Nothing. It would be one thing if this language was in a contract for actual employment, where you might get healthcare, retirement benefits and business cards.

This sort of language makes my blood boil. I’ve seen things like this with other publications (Conde Nast, for instance, has some pretty harsh language around movie rights), but nothing quite as bad as this.

This, my gentle readers, is why the future of journalism is in such perilous standing. If magazines don’t pay journalists, and then also make it impossible for them to otherwise earn a real living off of their work then one day there will be no journalists to work with.

My advice to any journalist faced with a clause like this: don’t sign it. Post your story on your personal blog, or sell it to another publication.

__

UPDATE: This, of course is pretty bad news for freelancers, but there are a few ways to fight back. I recently started offering an online video course teaching some of the tricks that I use to negotiate better contracts, and grow my freelancing business from nothing to becoming a New York Times bestselling author. It might be useful for you. Check it out.

National Novel Writing Month

I don’t write novels, but this morning I got a message from the website Webucator asking me for my thoughts on National Novel Writing Month. In particular they wanted to know what it means to write for a living. Regular readers will remember that I recently published a short ebook on the freelance writing career path called The Quick and Dirty Guide to Freelance Writing about how to attain that elusive dream of quitting your day job and working for yourself. So, perhaps, they wondered, I could share a few thoughts on how to write for a living.

I don’t write novels, but this morning I got a message from the website Webucator asking me for my thoughts on National Novel Writing Month. In particular they wanted to know what it means to write for a living. Regular readers will remember that I recently published a short ebook on the freelance writing career path called The Quick and Dirty Guide to Freelance Writing about how to attain that elusive dream of quitting your day job and working for yourself. So, perhaps, they wondered, I could share a few thoughts on how to write for a living.

What were your goals when you started writing?

Sometimes I feel like I didn’t choose to be a writer, but that writing chose me.I’d failed or been fired from every other job I’d tried over the years and writing was the only thing that I was ever good at. Part of the problem, of course, is that I have an almost adolescent rejection of authority and working on other people’s projects always seemed less fulfilling than working on my own things. I also have a predilection for exploration and adventure. Writing has given me an excuse to spend months at a time pursuing strange and unusual subjects and call it a career. As I mention in the book, my first real assignment came after I’d dropped out of graduate school and enrolled in a clinical trial for the erectile dysfunction drug Levitra. I thought that it was hilarious that I was going to be stuck in a room with 30 other dudes on penis-poppers and decided to write to Nerve.com to see if they wanted a feature on the subject. They did, and a writing career was born.

What are your goals now?

At first it was good enough to see my name in a magazine or newspaper. Getting a byline was such a buzz that I would probably have done it for free. Now, however, the luster has worn off a bit and I’m a little more picky about what sorts of assignments I take. A lot of publications don’t treat their writers very well. Boiler-plate contracts are often rigged against the writer and payment can take forever if the magazine is even a little bit disorganized. So while I still love the work (i.e. having mini adventures in the world and then coming back home and telling people about it) I am much more savvy at making the work that I do build into larger things.

What pays the bills now?

After about six years of freelancing exclusively for magazines I started to diversify my revenue streams. I had a pretty substantial body of work that I controlled the rights to, so I started to poke and prod magazines and newspapers in foreign markets to see if they’d be interested in buying reprints. Some time around 2008 I made $$25,000 on reprinting one story in 15 different countries and I realized that secondary markets could be more lucrative than the initial assignment fee. I began looking for other ways to make money on my writing and compiled some of my best stories into a book called The Red Market. While the book didn’t become an out-of-the-box bestseller, it established me as a serious journalist in a way that simply having a byline in a magazines never could have. It also opened upmarket for paid speaking engagements. I started giving lectures around the United States and Europe on the subject of organ trafficking. I started looking at magazines as incubators more lucrative projects. Now I only write stories in magazines if I plan to build it into something bigger. My third book A Death on Diamond Mountain, started out as a story in Playboy.

Assuming writing doesn’t pay the bills, what motivates you to keep writing?

At this point writing absolutely does pay the bills.

And optionally, what advice would you give young authors hoping to make a career out of writing?

It’s counterintuitive, but the most important thing you can do as a writer is say “No” to assignments. It’s very easy to fall into the trap of believing that simply having a byline is payment enough. This sort of mindset will doom any aspirations that you might have to make writing a living. There are a lot of bad deals out there, and if you don’t stand up for your work then why should you expect someone else to do it for you? Treat your writing career as a business negotiate every deal you have with an eye to building the career that you want.

The Current talks Red Markets

Listen to the CBC’s coverage of “The Red Market” where I talk bone thieves, blood farmers and things that go bump in the night.

Listen to the CBC’s coverage of “The Red Market” where I talk bone thieves, blood farmers and things that go bump in the night.

Tavis Smiley and The Red Market

Tavis Smiley who has one of the most thought provoking talk shows on television, had me on to talk about how red market transactions disproportionately affect poor people and send flesh up the human supply chain.

Tavis Smiley who has one of the most thought provoking talk shows on television, had me on to talk about how red market transactions disproportionately affect poor people and send flesh up the human supply chain.

See the video of the interview on PBS.

New York Times Review

Need a Kidney? A Skull? Just Bring CashMichiko Kakutani June 16 2011Whereas black markets trade in illegal goods like guns and drugs, the “red market,” the journalist Scott Carney says in his revealing if somewhat scattershot new book, trades in human flesh — in kidneys and other organs, in human corneas, blood, bones and eggs. Many of the real-life examples he cites in this chilling volume cannot help but remind the reader of a horror movie, or of Kazuo Ishiguro’s devastating dystopian novel “Never Let Me Go” (2005), in which we learn that a group of children are clones who have been raised to “donate” replacement body parts.

Need a Kidney? A Skull? Just Bring CashMichiko Kakutani June 16 2011Whereas black markets trade in illegal goods like guns and drugs, the “red market,” the journalist Scott Carney says in his revealing if somewhat scattershot new book, trades in human flesh — in kidneys and other organs, in human corneas, blood, bones and eggs. Many of the real-life examples he cites in this chilling volume cannot help but remind the reader of a horror movie, or of Kazuo Ishiguro’s devastating dystopian novel “Never Let Me Go” (2005), in which we learn that a group of children are clones who have been raised to “donate” replacement body parts.

In “The Red Market” Mr. Carney recounts the story of a police raid on a dairy farmer’s land in a small Indian border town that freed 17 people who had been confined in shacks and who said they’d been bled at least two times per week. “The Blood Factory,” as it was called in the local press, he writes, “was supplying a sizable percentage” of the city hospitals’ blood supply.

Mr. Carney also investigates the bone trade in India — for almost 200 years, “the world’s primary source of bones used in medical study” — and tries to track down the head of a grave robbing ring in West Bengal, who, according to police, was pilfering corpses from cemeteries, morgues, and funeral pyres and employed “almost a dozen people to shepherd the bones through the various stages of defleshing and curing.”

A contributing editor at Wired magazine, Mr. Carney writes with considerable narrative verve, slamming home the misery of what he has witnessed with passion and visceral detail. His book does not attempt to provide a comprehensive picture of red markets in the world today. Much of Mr. Carney’s reporting focuses on India (where he lived and worked for a decade), while dealing only cursorily with human organ trafficking in other hot spots like the Philippines and Brazil.

In one chapter Mr. Carney describes an impoverished Indian refugee camp for survivors of the 2004 tsunami that was known as Kidneyvakkam, or Kidneyville, because so many people there had sold their kidneys to organ brokers in efforts to raise desperately needed funds. “Brokers,” he writes, “routinely quote a high payout — as much as $3,000 for the operation — but usually only dole out a fraction of the offered price once the person has gone through it. Everyone here knows that it is a scam. Still the women reason that a rip-off is better than nothing at all.” For these people, he adds, selling organs “sometimes feels like their only option in hard times”; poor people around the world, in his words, “often view their organs as a critical social safety net.”

Toward the end of the book Mr. Carney notes that “criminal and unethical red markets are far smaller than their legitimate counterparts.” According to the World Health Organization, he writes, “about 10 percent of world organ transplants are obtained on the black market.” But he emphasizes that “red markets are now larger, more pervasive, and more profitable than at any other time in history,” and that “globalization has made the speed and complexity of these markets bewildering.”

The most alarming allegations cited in this book come from a 2006 report released by David Kilgour, a former member of the Canadian Parliament, and the human rights lawyer David Matas, which suggested that vital organs (including kidneys, corneas and livers) had been harvested on a large scale from executed members of Falun Gong, a banned spiritual group in China. The Chinese government denied the allegations.“

No one is saying the Chinese government went after the Falun Gong specifically for their organs,” Mr. Carney writes, “but it seems to have been a remarkably convenient and profitable way to dispose of them. Dangerous political dissidents were executed while their organs created a comfortable revenue stream for hospitals and surgeons, and presumably many important Chinese officials received organs.”

Mr. Carney is not able to verify the Kilgour-Matas report independently. For that matter, his overall approach here tends to be heavily anecdotal and selective, focusing on horror stories like the kidnapping of a young Indian boy, who, the police said, was brought to an orphanage “that paid cash for healthy children” and then “exported the children to unknowing families abroad.”

As Mr. Carney sees it: “Eventually, red markets have the nasty social side effect of moving flesh upward — never downward — through social classes. Even without a criminal element, unrestricted free markets act like vampires, sapping the health and strength from ghettos of poor donors and funneling their parts to the wealthy.”

His book is filled with harrowing stories in which the destitute and desperate end up sacrificing their bodies for the sake of a few dollars that fail to change their lives.

In one chapter Mr. Carney writes that most egg donors in Cyprus — which “had more fertility clinics per capita than any other country” — come from the relatively small population of poor Eastern European immigrants who are “eager to sell their eggs at any price.” A donor in Cyprus will probably get paid a few hundred dollars for her eggs, Mr. Carney estimates, while customers — often from Western Europe — will pay $8,000 to $14,000 for full-service egg implantation with in vitro fertilization in Cyprus, “about 30 percent less than the next cheapest spot in the Western world.”

Globalization has also brought what Mr. Carney calls the “fertility tourism industry” to India, which, he says, “legalized surrogacy in 2002 as part of a larger effort to promote medical tourism.” At the Akanksha Infertility Clinic (which was featured in an “Oprah” segment), he says, surrogates, who make between $5,000 and $6,000, live in residential units, where “they will spend their entire pregnancies under lock and key.” The clinic charges between $15,000 and $20,000 for the entire process, he reports, “whereas in the handful of American states that allow paid surrogacy, bringing a child to term can cost between $50,000 and $100,000.”

“Before India, only the American upper classes could afford a surrogate,” Mr. Carney writes. “Now it’s almost within reach of the middle class. While surrogacy has always raised ethical questions, the increasing scale of the industry makes the issue far more urgent. With hundreds of new clinics poised to open, the economics of surrogate pregnancies are moving faster than our understanding of its implications.”

In addressing such ethical questions throughout this grisly but fascinating volume, Mr. Carney forces the reader to think about the moral issues raised by advances in medicine. His book also asks us to re-evaluate the roles that privacy, anonymity and altruism play in the current “system of flesh exchange” — which, as disturbing as it is to contemplate, is subject, like those for other commodities, to the brutal marketplace equations of supply and demand.

"Invasion of the Body Snatchers"

Invasion of the Body SnatchersKidneys are the most popular — bought and sold on the global black market at a rate of at least 20,000 per year. Blood, tissue, skin, corneas and eggs are also highly valued. Human bones are a centuries-old mainstay.

Invasion of the Body SnatchersKidneys are the most popular — bought and sold on the global black market at a rate of at least 20,000 per year. Blood, tissue, skin, corneas and eggs are also highly valued. Human bones are a centuries-old mainstay.

The demand outstrips the supply, and so millions of variations on that old urban legend — some unsuspecting victim waking up in a bathtub in Vegas, missing a kidney — actually exist: People snatched off the street in India and China, held for years as chained-up blood donors. Prisoners in China forced to donate body parts, plucked apart, sometimes alive, sometimes without anesthesia. Entire villages, like the Baseco slum in the Philippines, where the bulk of inhabitants have only one kidney — having sold the other off for a few hundred dollars to pay rent or buy food or medicine for a sick relative.

Read Maureen Callahan’s full story at the NY Post

NPR: Blood, Bones And Organs

Journalist Scott Carney figures he’s worth about $250,000, but that number isn’t based on his savings or his assets; it’s what Carney thinks his body would fetch if it were broken down into individual parts and sold on what he calls the “red market.” In his new book, also called The Red Market, Carney explores the shadowy but lucrative global marketplace for blood, bones and organs. He tells NPR’s Melissa Block that despite being underground, there’s no question the red market is thriving. “It’s really hard to get accurate figures on what the illegal market is on body parts, but I’m figuring it’s definitely in the billions of dollars,” Carney says.

Journalist Scott Carney figures he’s worth about $250,000, but that number isn’t based on his savings or his assets; it’s what Carney thinks his body would fetch if it were broken down into individual parts and sold on what he calls the “red market.” In his new book, also called The Red Market, Carney explores the shadowy but lucrative global marketplace for blood, bones and organs. He tells NPR’s Melissa Block that despite being underground, there’s no question the red market is thriving. “It’s really hard to get accurate figures on what the illegal market is on body parts, but I’m figuring it’s definitely in the billions of dollars,” Carney says.

‘When You’re At Your Most Desperate Place … The Brokers Come In’ As part of his research, Carney visited an Indian refugee camp for survivors of 2004’s massive tsunami. Today, the camp is known by the nickname Kidneyvakkam, or Kidneyville, because of how common it is for the women who live there to sell their kidneys. “The women are just lined up,” Carney says. “They have their exposed midriffs and there are all these kidney extraction scars because when the tsunami happened, all these organ brokers came in and realized there were a lot of people in very desperate situations and they could turn a lot of quick cash by just convincing people to sell their kidneys.”

Photos from The Red Market

For six years I didn’t only collect stories from people who supplied their flesh on the red market. I also took pictures. Here is a small set of photos that appeared in the book. Above is Fatima whose daughter Zabeen was kidnapped from a slum in Chennai and sold to an Australian family through a network of unwitting adoption agencies. Please don’t reproduce these without my permission.

For six years I didn’t only collect stories from people who supplied their flesh on the red market. I also took pictures. Here is a small set of photos that appeared in the book. Above is Fatima whose daughter Zabeen was kidnapped from a slum in Chennai and sold to an Australian family through a network of unwitting adoption agencies. Please don’t reproduce these without my permission.

Click here to see the gallery.

India's Maoists

Since 2000 more than 10,000 people have died and 150,000 displaced by a Maoist insurgancy in India. In 2007 I traveled to Chhattisgarh, India with Jason Miklian to report how a police-funded civilian counter insurgency called “Salwa Judum” had only made the conflict worse. Now with warlords, communist ideologues and out of control military forces there are few places for civilians to find safety. While this story never appeared in a major publication, a later version that traced the connections between the mining industry and Maoism appeared in Foreign Policy in September 2010 under the title “Fire in the Hole”

Since 2000 more than 10,000 people have died and 150,000 displaced by a Maoist insurgancy in India. In 2007 I traveled to Chhattisgarh, India with Jason Miklian to report how a police-funded civilian counter insurgency called “Salwa Judum” had only made the conflict worse. Now with warlords, communist ideologues and out of control military forces there are few places for civilians to find safety. While this story never appeared in a major publication, a later version that traced the connections between the mining industry and Maoism appeared in Foreign Policy in September 2010 under the title “Fire in the Hole”

Click here to see the photo gallery

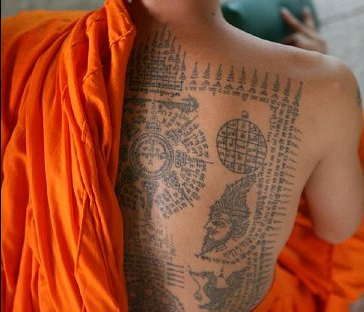

Thai Protection Tattoos

Can a tattoo stop a bullet? A centuries old thai tattoo tradition teaches that indeed, the sacred scriptures can have protective powers. In 2007 I traveled to the remote wat bang pra temple to interview the artistic masters who have spent their lives perfecting the art. I reported the story for National Public Radio which you can listen to here. But what what is a radio story without great photos?

Can a tattoo stop a bullet? A centuries old thai tattoo tradition teaches that indeed, the sacred scriptures can have protective powers. In 2007 I traveled to the remote wat bang pra temple to interview the artistic masters who have spent their lives perfecting the art. I reported the story for National Public Radio which you can listen to here. But what what is a radio story without great photos?

Click here to see the gallery of photos here.

Salon Review: Flesh for sale

During the mid-2000s, Scott Carney was living in southern India and teaching American anthropology students on their semester abroad when one of his charges died, apparently a suicide. For two days, he watched over her body while the provincial police investigated her death, reporters bribed their way into the morgue to photograph the newsworthy corpse, local doctors performed an autopsy, and ice had to be rounded up to retard decomposition. Finally, his boss asked Carney to take pictures of the girl’s mangled remains for analysis by forensic experts back in the States.

During the mid-2000s, Scott Carney was living in southern India and teaching American anthropology students on their semester abroad when one of his charges died, apparently a suicide. For two days, he watched over her body while the provincial police investigated her death, reporters bribed their way into the morgue to photograph the newsworthy corpse, local doctors performed an autopsy, and ice had to be rounded up to retard decomposition. Finally, his boss asked Carney to take pictures of the girl’s mangled remains for analysis by forensic experts back in the States.

(review by Laura Miller)

Border Wars

Bangladesh shares a border with only two other countries: the republic of India and the dictatorship of Burma. With climate change threatening much of the low-lying country refugees will have to go somewhere. And India has decided to prepare for the influx by building a wall and shooting anyone who tries to cross it. In January 2011 I traveled to Bangladesh and India with Jason Miklian and Kristian Hoelscher on an assignment for Foreign Policy.

Bangladesh shares a border with only two other countries: the republic of India and the dictatorship of Burma. With climate change threatening much of the low-lying country refugees will have to go somewhere. And India has decided to prepare for the influx by building a wall and shooting anyone who tries to cross it. In January 2011 I traveled to Bangladesh and India with Jason Miklian and Kristian Hoelscher on an assignment for Foreign Policy.